Ideas and Evidence

Science and scientific evidence

Watch the video below, ‘what’s in the box’ then read on.

Were you able to work out what was in the box from the sounds? The ideas you suggested were not based on pure guesswork, were they? They were based on the evidence available to you.

Suppose you are now given another box but this time, the box is sealed. You shake it and it rattles. It sounds a bit like a couple of metal spoons, but then again, perhaps it’s three spoons … or a fork and spoon. Is there a way to know which theory is right? Suppose you’re now given access to an X-ray machine. Does that help?

Suppose you X-rayed the box and saw nothing inside but the box rattled when you shook it, what would that tell you?

Conclusive evidence

Sometimes, when you’re investigating different possibilities, the evidence for one theory or another becomes overwhelming and everyone agrees on the proper conclusion.

In science, this is often the way it seems to work. Mind you, there is a reason for this. The science you study at school tends to focus on the ideas that are now well established in science. Even with this said, science is a particularly good way to test theories. Here’s why:

Scientific evidence is evidence you can detect using your senses or sensors. The evidence must be objective which means that everyone can see it.

Suppose in contrast you stub your toe and begin to hop around the room, yelling in agony. “Oi!” says your unsympathetic friend, “Stop making a fuss about nothing.” In this case, the evidence is subjective. The pain signals that travel from your toe to your brain are felt only by you, so only you can decide how much it hurts.

Suppose in contrast you stub your toe and begin to hop around the room, yelling in agony. “Oi!” says your unsympathetic friend, “Stop making a fuss about nothing.” In this case, the evidence is subjective. The pain signals that travel from your toe to your brain are felt only by you, so only you can decide how much it hurts.

Galileo: the father of modern science

Galileo is widely considered to be one of the greatest scientists who ever lived. He is said to be the first scientist who used experiments as a way to test theories.

In the video below, we see how he came up with one of his most famous theories. This idea was that all objects, regardless of their weight, fall with the same speed.

To test his theory, Galileo did a range of experiments. It is sometimes said that in one of these experiments, Galileo dropped two balls from the top of the leaning tower of Pisa. One ball was wooden and one was lead. Historians think this probably didn’t happen, although Galileo did, they say, suggest that this would be an exciting way to see his theory working in practice.

To test his theory, Galileo did a range of experiments. It is sometimes said that in one of these experiments, Galileo dropped two balls from the top of the leaning tower of Pisa. One ball was wooden and one was lead. Historians think this probably didn’t happen, although Galileo did, they say, suggest that this would be an exciting way to see his theory working in practice.

Air resistance changes how the balls fall. It is as if one ball has a parachute.

Interestingly, Galileo’s experiment was tried years later: Two balls were dropped from Pisa but the surprise was that the lead ball hit the ground first. Why? Galileo knew why. He had already predicted that this would happen. If gravity were the only force at work, the balls would have hit the ground together, but air resistance also plays a role.

A couple of hundred years later, a chance came for scientists to see this experiment without air.

In 1971, Commander David Scott (pictured right) from the Apollo 15 mission, put Galileo’s idea to the test. In front of a live television audience, in one hand, he held a hammer and in the other, a feather.

In 1971, Commander David Scott (pictured right) from the Apollo 15 mission, put Galileo’s idea to the test. In front of a live television audience, in one hand, he held a hammer and in the other, a feather.

Scott dropped them at the same time … and scientists nodded with satisfaction. Just as Galileo had concluded hundreds of years before, it really is the case that all objects released together fall at the same rate.

So in science, physical evidence is used to support and test ideas.

Religion and Religious evidence

Here is some of the evidence that religious people describe as supporting their belief in a Creator God. As you’ll see, it is harder to be certain about these claims. There are other ways to interpret the same observations:

The Argument from Design

You probably agree that our Universe is amazing. This is the evidence that we all see – a beautiful Universe. Some people see the beauty of nature as evidence that our Universe is God’s brainwave; Others say that this is how nature turned out and that we have learned to appreciate it.

The Cosmological Argument

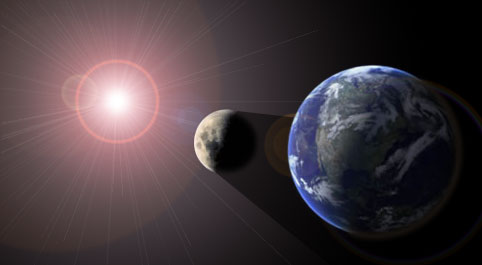

Our Earth is sometimes called the ‘Goldilocks planet’. This is the place where everything is ‘just right’ for life. There’s water, warmth and everything that’s needed for life to start.

Some people see the development of life on Earth as evidence of God’s Creative work in progress. Others do not. They say that things could have turned out differently and in that case, we would not be here.

A passion for exploring

Some religious people see the existence of science itself as evidence for the idea that God exists. God created a universe which can be explored using science and He gave humans a passion for exploring, they say. Once again, this is far from the only way to explain why people are attracted to puzzles and mysteries.

Why believe?

Evidence in religion is important as a way to justify and test beliefs but it is not the end of the story. There are other reasons to believe that something might be true. In our scientific age, that might sound like a cheat! Surely you should only believe what you can see, hear, taste, touch and feel! But as we’ll see on the next page, people believe things for a whole host of reasons. This presents the rest of us with a challenge when we listen to people saying what they believe. Somehow we have to decide which reasons are reasonable and which are not.

Evidence in religion is important as a way to justify and test beliefs but it is not the end of the story. There are other reasons to believe that something might be true. In our scientific age, that might sound like a cheat! Surely you should only believe what you can see, hear, taste, touch and feel! But as we’ll see on the next page, people believe things for a whole host of reasons. This presents the rest of us with a challenge when we listen to people saying what they believe. Somehow we have to decide which reasons are reasonable and which are not.

Just for starters, read the argument by Blaise Pascal below. In your view, is this a good reason for believing in God?

The Argument for God presented by Blaise Pascal

The Argument for God presented by Blaise Pascal

A mathematician living in the seventeenth-century came up with this idea, which sounds something like a gamble. He said, if you believe in God and you turn out to be wrong, you won’t be any worse off. After all, there is no God to punish you for getting it wrong.

But if you deny God and He turns out to be real … and angry, this would be a serious mistake. On this basis, the sensible choice is to believe in God.